There seems to be confusion, among the public in general but also among professionals, about what smart beta (or “factor”) funds really are. Are they passive? Are they active?

This blog will try to help investors find answers.

Broadly speaking, a smart beta fund is a fund that is managed according to some sort of quantitative algorithm in order to remove arbitrary human judgement from money management as much as possible. At best, this algorithm is backed by several rigorous independent research papers from highly reputed university professors. At worst, it is based on back-tests run by investment companies in the hopes of designing an investment product that will generate a lot of fee income. In any case, the research supporting the algorithm suggests a process for selecting securities or a weighting scheme that promises an above-market expected return. Smart beta funds are dubbed “smart” because they promise the market’s rate of return plus a premium.

Smart beta products include single-factor investment vehicles (value, small cap, low volatility, high dividend, quality… you name it!) and multi-factor funds. In the current environment of low expected returns, many investors do not accept the market’s rate of return. This is clearly seen in large pension funds and endowment funds that hold low weights in bonds and high weights in alternative investments. Our low-return environment is also responsible for investors’ aversion to high fees, which make low returns even lower. Smart beta funds seem to offer the best of both worlds: low fees plus a (presumably) above-market expected return. Who would say no to that?

But let’s get back to our initial question, our Mini Wheats–like problem: Who are you, Smart Beta? Active and delicious? Or passive and nutritious?

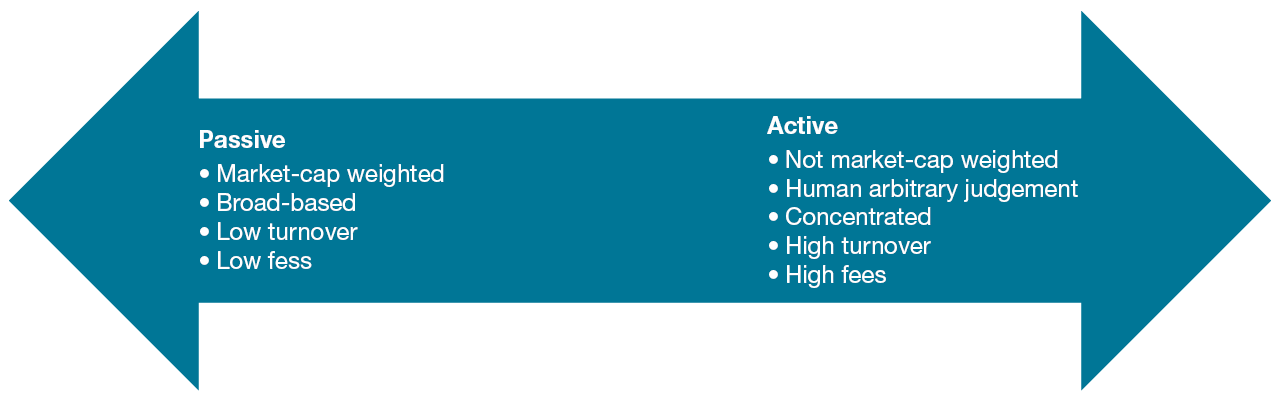

For me, the perfect passive fund is one like the BMO S&P/TSX Capped Composite Index ETF for Canadian equity or the Vanguard Total Market ETF for U.S. equity. Here are the features I would want to see in an ideal passive fund:

My ideal active fund has concentrated holdings (let’s say twenty or fewer), with security weights that are determined purely by the manager’s intuition. As the number of securities held by an actively managed fund converges to the index’s securities count, its return will converge toward the market rate of return. This is called closet indexing. Furthermore, the ideal active fund has a very high rate of turnover, as investment ideas that were good yesterday rapidly become stale in a fast-paced world. Finally, of course, the perfect actively managed fund charges high fees, which is logical since its managers are serial market beaters, who require that they be compensated accordingly.

You might have guessed that some actively managed funds can bear passive attributes, for instance, a traditional stock picker who tends to hold no more than 15 stocks, keeps them several years and charges low fees. Conversely, some passive funds have active attributes. For example, the iShares S&P/TSX60 Index ETF (ticker: XIU) holds a narrow group of 60 stocks that are chosen subjectively by a selection committee for sector-diversification purposes. My point is this: apart from some extreme examples, active and passive investments are not simply black or white. They are shades of grey.

Most portfolio managers at PWL Capital use funds from Dimensional Fund Advisors Canada to tilt equity portfolios toward investment factors. These funds come with two multi-factor structures: Core and Vector. The Core funds hold most of the liquid stocks in a market (Canadian, U.S. and international developed & emerging) with above-market weights in securities showing lower price-to-book ratios (value stocks), lower market cap and higher profitability. The Vector funds put an even heavier tilt toward these characteristics—to such an extent that they exclude a large number of securities determined to have low expected returns (very large growth stocks, for example). In a nutshell, Core funds are very broad-based, while Vector funds are narrower but still extremely diversified. In addition, DFA equity funds generally have a low turnover and low (albeit not the lowest) fees. Table 1 below outlines some key characteristics of these funds.

| Fund | Number of securities held | Turnover | MER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Core Equity | 428 | 3.1% | 0.33% |

| Canadian Vector Equity | 375 | 8.2% | 0.41% |

| U.S. Core Equity | 2,403 | 3.5% | 0.28% |

| U.S. Vector Equity | 2,092 | 4.6% | 0.40% |

| International Core Equity | 7,231 | 1.7% | 0.48% |

| International Vector Equity | 5,480 | 2.8% | 0.60% |

To summarize, DFA funds are

In my view DFA funds are, on balance, much closer to a pure passive fund than an active one.

I believe it’s misguided to make blanket statements about smart beta funds. Each fund should be analyzed on its own merits. Some smart beta ETFs may have no characteristics of a passive fund. Others may be much closer. This article proposed a framework to identify the passive or active nature of the funds you hold. If you adhere to the passive philosophy of investing, you should ideally hold funds that align with this, to help you stick to your long-term strategy and achieve your financial objectives.